By Stuart Mann

When Andrew Solomon was a little boy, his mother said to him, “The love you have for your children is like no other feeling in the world, and until you have children, you don’t know what it feels like.”

He has spent the past decade investigating just how deep that love can be. In his bestselling book, Far from the Tree: Parents, children and the search for identity, he tells the stories of parents who not only learn how to deal with their exceptional children but also find profound meaning in doing so.

Mr. Solomon was the guest speaker at the fifth annual Richard Gidney Seminar on Faith and Medicine, held at Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, on April 3. The annual event is hosted by the Diocese of Toronto, Mount Sinai and SickKids hospital. It brings together health care workers and those who provide spiritual and religious care for conversations around holistic patient care.

Mr. Solomon, a writer based in New York, moved many in the audience to tears as he recounted the experiences of parents who raised children whom society has traditionally rejected – dwarves, the transgendered, autistic people, schizophrenics, deaf people and others. In many cases, the parents were told to let their children die at birth or put them in institutions. They often encountered fierce resistance from neighbours, schools, churches and places of work.

“The irony at the centre of the book was that most of the parents I interviewed had ended up in one way or another grateful for the lives that they would have done anything to avoid,” he said.

His journey into this other world began about 20 years ago, when his editors at the New York Times Magazine asked him to write an article about deaf culture. He was taken aback by the assignment, partly because he had no idea that deaf people had a culture. “I always thought deafness was a disability – those poor people, they couldn’t hear, what a tragedy it was for them, we should do something to help them.”

Then he went into the deaf world – to deaf clubs, deaf theatre and even attended the Miss Deaf America contest in Nashville. “As I went deeper and deeper into the deaf world, I came to understand that deafness was a culture and that the people I was meeting had a strong sense of cultural identity,” he said.

A major turning point came when he attended a meeting of the National Association of the Deaf. “I remember thinking that I wished I were deaf,” he said. “There were all of these people rushing towards one another, their hands waving through the air in conversation, and I thought, wouldn’t it be amazing to be a part of this society? It was a beautiful world.”

He realized that those deaf people were the children of parents who could hear. Historically, he said, the parents of deaf children often pushed their kids towards learning lip reading or oral speech, often to their detriment. It wasn’t until the children had found their own culture, where they were accepted by their peers for who they were, that they really began to thrive.

“As many of those children discovered deaf culture in adolescence and thereafter, it came as a glorious liberation for them, and then they and their parents negotiated their relationship around that,” he said.

He found this was true for many other groups of exceptional children. As they found and then lived in their own culture, they blossomed and many of their conflicts and anxieties were resolved.

For their parents, this often took a long time to accept. “Acceptance is a process, and it takes time,” he said. “It is a process that has to unfold in every family, and it takes time in every family. I think those themes of love and acceptance run throughout religious doctrine.”

Most of the parents he talked to, upon finding their children were different, first experienced outrage, and then bewilderment and then celebration. “These don’t always happen in order and they’re always in flux. There’s a constant attempt to move through these various stages toward a greater enlightenment in the interaction between parent and children.”

He quoted from the gnostic Gospel of St. Thomas. “Jesus says, ‘If you bring forth what is within you, then what is within you will save you; if you do not bring forth what is within you, then what is within you will destroy you.’ I always wish those words were canonical because I feel that an awful lot of the journey of the families I was looking at was their journey toward bringing out what was within them, acknowledging it, acknowledging it openly, and allowing it to define the experience of the family in a profound and productive way.”

He questioned whether the medical community, in its efforts to find “cures” for exceptional children, take into account the great strides those children have made just as they are. “I’m a great believer in social progress, and I’m a great believer in scientific progress, but I sometimes think that they haven’t noticed each other,” he said. “I feel like there are these wonderful breakthroughs that come in social progress which are threatened to become immediately irrelevant because of the scientific progress.

“There’s the question of whether people want to be cured or whether they feel their condition defines them and they don’t want to be cured,” he said. “A person with autism told me, ‘When parents say, ‘I wish my child did not have autism,’ what they’re really saying is that they wish the autistic child they had did not exist, that I had a different, non-autistic child instead. This is what we hear when you mourn over our existence. This is what we know when you pray for a cure, that you’re fondest wish is that someday we will cease to be and a stranger you can love will move in behind our faces.’ That’s an extreme point of view, but it was shared by many of the people I talked to. They said I am who I am. I have come to have an understanding of myself as who I am, and I am just as human as anyone else.”

He said these children, accepted and allowed to be who they are, have great potential to change society. He quoted St. Paul’s words in 2 Corinthians: “Therefore, I take pleasure in infirmity, for when I am weak, then I am strong.”

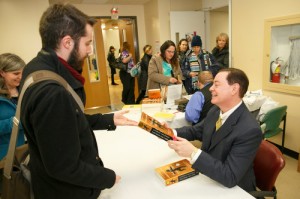

At the end of Mr. Solomon’s talk, the audience of about 200 gave him a long ovation. Afterwards, he signed copies of his book.

The lecture series, celebrating its fifth anniversary, is named after the Rev. Richard Gidney, an Anglican chaplain and the diocese’s Coordinator of Chaplaincy who died in 2000. Previous speakers have included Bishop Mark MacDonald, Canada’s national indigenous bishop, and author Ian Brown. This year’s lecture also welcomed two new funding partners, The Toronto Board of Rabbis and the Anglican Foundation of Canada.

Learn more about healing ministries in the Diocese of Toronto.