By Diana Swift

Progressing from personal acts of charitableness to working for systemic justice was the topic of the keynote address at “Transformed Hearts, Transforming Structure,” the diocese’s Outreach & Advocacy Conference held Oct. 27 at Havergal College in Toronto.

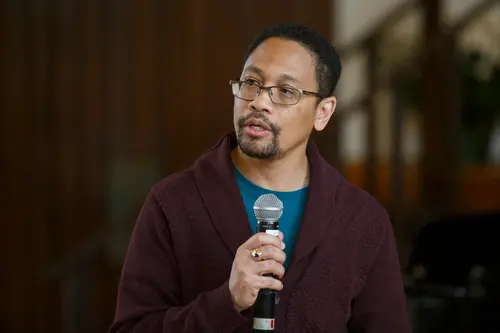

We have all acted charitably out of compassion for another’s need at some point, said André Lyn, a social justice activist who works with Ontario’s Antiracism Directorate and the Ontario Black Youth Action Plan. “An individual act of compassion connects us with the love of God within us by enacting that love.”

But occasions for situational acts of charity sometimes present us with a “compassionate predicament,” in which showing empathy involves a certain struggle – for example, when a needy outstretched hand is asking for money but the donor prefers to give food, believing the recipient will use the money for drugs or alcohol. “Who are we to judge if they want to use the money for drugs?” asked Mr. Lyn. “Food does not address their need or the roots of their addiction.” And what is a vice to us can be their means of connecting with their society and escaping harsh reality.

Compassionate charity is different from compassionate justice, he stressed. “Charity is what we do most often. It’s easier to do than justice.” It may involve volunteering at food or clothing drives, giving money to a social cause or handouts on the street. “It has its place. Charity is a type of compassion that meets someone’s immediate needs and temporarily eases the effects of suffering,” he said. It is necessary and important, but it is temporary and insufficient.

Compassionate justice is much more difficult and slow-moving, as it addresses the root causes of suffering – poverty, homelessness, mental health, addictions and discrimination. It seeks to correct the inequities that are endemic to our religious, educational and legal institutions, and its progress is slow but incremental. “If charity is about transforming hearts, justice is about transforming structures, systems, and institutions. It is the social and political form of compassion,” he said. It is wide-ranging, and it effects lasting change.

Apathy is the enemy of such justice, he said, quoting Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel’s observation that the opposite of love is not hatred but indifference. He used an engaging animal parable to show the wide-ranging ill effects of indifference. In the parable, a farm mouse meets total indifference from a chicken, a pig and a cow when he reports the introduction of a mousetrap to the farmhouse. The trap snares a poisonous snake, which bites the farmer’s wife; eventually, the apathetic chicken and pig are sacrificed for the wife’s recuperation and the cow, ultimately, for her funeral banquet.

Mr. Lyn also cited the famous poem of German pastor Martin Niemöller, about how he failed to speak out when the Nazis came for the socialists, the trade unionists and the Jews because he was not one of any of those, until finally they came for him and there was no one left to speak for him.

Occasions to address systemic inequities are all around us, said Mr. Lyn, referring to two recent incidents in which anti-black slurs were written on the same property of a church in the diocese. Compassionate prayers and support at a special service were offered by the area bishop and others, he said, but that did not go far enough. “We had an opportunity to address a structural and systemic injustice in society,” he said, so his group asked the area bishop if there was a diocesan policy to address hate crimes. Not surprisingly, the answer came back no.

“This sort of silence has an unintentional impact,” he said. “It has allowed such atrocities to go unchallenged and unaddressed systemically.” But now he and his colleagues have committed to working actively with the College of Bishops to address this racial issue in a structural way.

Mr. Lyn urged Anglicans not to give up personal charitableness but to move from personal compassion and transformed hearts at the individual level into collective compassion and broader solidarity at the system level, and to commit to active outreach and active advocacy.

This will require people to be audacious and bold, he said, urging the audience to harness their collective compassion and inequity, suffering, and hurt toward transforming structures by serving at any level. “There is no better time to become involved than the present,” he said. “We need to become agents of change.”

The conference also featured 10 workshops on significant outreach and advocacy topics, including housing for vulnerable seniors, grassroots initiatives against poverty, and Indigenous identity and water protection.

Ministry helps ex-prisoners re-enter society

One of the most challenging but rewarding forms of Christian service is prison ministry, as was evident in a workshop led by the Rev. Mark Stephen and Jerome Friday of The Bridge Prison Ministry, which is supported by FaithWorks, the diocese’s annual outreach appeal. The Bridge works with offenders at the Ontario Correctional Institute in Brampton, before and after their release back into society.

“The lives of these men are broken,” said Mr. Stephen, a community outreach worker and deacon at St. Joseph of Nazareth, Bramalea. “Often they can’t go home or have no home to go to. They can’t return to the community where they committed their crimes.”

Mr. Friday outlined The Bridge’s 16-week pre-release, volunteer-run in-prison program of group discussions. These are designed to help inmates confront their personal responsibility and rebuild their self-esteem by addressing 22 core issues, including acceptance, despair, love, respect, guilt, shame, and hope. “These discussions help them change the negative thought patterns that landed them where they are,” he said.

“These men are scarred and are often from dysfunctional homes, and have experienced childhood events that were never addressed,” he said. “They’ve been told they’re worthless, but we try to get them to see that, yes, they’ve made mistakes but they themselves are not mistakes.”

At first mistrustful and unwilling to share their stories, the men gradually open up and become friendly and mutually supportive.

But even with four months of psychological preparation, re-entering the community is difficult. They have a criminal record, inadequate ID for today’s security-obsessed society, and no fixed address. Getting an OHIP card, obtaining employment or renewing their medications for ADHD or depression is difficult. They are released from prison with one day’s pay and can’t even cash the government cheque they receive.

At the time of release, Mr. Stephen meets the ex-offender at the gates and The Bridge provides seasonal clothing, a backpack and transportation to shelter. “Some of the men don’t even know how they’ll survive the first day out of prison,” he said. Later, The Bridge provides a re-conditioned cellphone with a month’s service and helps with finding stable shelter, getting essential ID and obtaining work, which is greatly facilitated by working through the buffer of employment agencies. “Within three months, 74 per cent of our ex-offenders – some in their 60s and 70s – are employed and living in stable housing, and their addictions are under control,” Mr. Stephen said.

But the first stop after release is Tim Horton’s for coffee after years of the undrinkable prison brew. “Sometimes they can’t even order their own coffee, so I always order everyone a double- double,” he said.

Migrant workers find support in Anglican churches

Each year, almost 40,000 migrant agricultural workers from Mexico, the Caribbean and other countries spend six to eight months in Canada planting and harvesting the crops that put an abundance of food on our tables.

Churches in the diocese are working on pastoral and practical fronts to make the newcomers’ experience in Ontario a better one. This was made clear at a workshop led by the Rev. Canon Ted McCollum, incumbent St. Paul, Beaverton, and the Rev. Augusto Nunez, priest-in-charge of St. Saviour, Orono.

Both these parishes and others offer migrant-worker programs with special services in Spanish, liturgical and musical participation by the Spanish-speaking workers. “Our first focus is spiritual, to help them to know Christ and provide a house of worship with services in Spanish,” said the Peruvian-born Mr. Nunez.

This spiritual care provides a buffer for the workers, who are often dealing with the mental and emotional stress of extended separation from family. Recently St. Paul’s (“San Pablo,” as the workers call it) provided pastoral support for a young father whose two-week-old son had died in Mexico before he had the chance to see him.

St. Paul’s program, which began in 2009 and collaborates with other migrant-worker groups in the region, addresses worldlier needs as well, such as car transportation to and from town. It helps with reconditioned bicycles, road and equipment safety, athletics and social life. In addition to weekly soccer games and barbecues, workers are brought together at health fairs with barbers, dentists, doctors, nurses and, very importantly, physiotherapists.

“These men work 10 hours a day on their knees and this takes a huge physical toll,” said Canon McCollum “It’s touching to see how happy some are to get the physiotherapy help they never had before.”

The churches also work tactfully with farm owners to determine how best they can help, and they connect the workers with local communities. “We’ve even had local people attend our Wednesday evening Spanish services,’” he said.

Not least, the program increases awareness of the large contribution the workers make to local life. “They spend $300,000 locally on food and other purchases,” he said. As their numbers swell the local population, services improve. “Thanks to them, our area met the threshold to qualify for a nurse practitioner, which benefits everyone.”

The workers send 80-90 per cent of their earnings home. “They’re phenomenally dedicated. Many of their kids have been able to become doctors, lawyers and engineers.” They pay all relevant Canadian taxes and deductions, even premiums for unemployment insurance, which they will never collect.

Church outreach programs need not be confined to rural areas. In the urban setting, they can also help visiting workers employed in restaurants and hotels.

Diana Swift is a freelance writer.